In March 1897, President William McKinley was sworn in, replacing Grover Cleveland, who had vowed neutrality in the Cuban affair. McKinley was taunted by the war hawks in government, finance and the media for his own failure to go to war right away. But the gears kept turning at the Navy, under Secretary John Long and his assistant Secretary Theodore Roosevelt; by the end of June, the Navy had adopted the 1896 war plan. In August, Long went on vacation, leaving Roosevelt at the helm. President McKinley invited Teddy for at least two personal discussions, at which time the acting Secretary acquainted the President with the ONI’s suggestions. [1] McKinley was apparently impressed with both Teddy and the plan.

Lacking a pretext for such a war, someone in Navy leadership ordered the state-of-the-art battleship U.S.S. Maine to visit Havana Harbor in December. The mission of the Maine is not entirely clear – some sources say it was to evacuate Americans if war broke out, but others point out that the ship would have little room for evacuees, loaded as it was with tons of ammunition. As George J.A. O’Toole described it: “a friendly visit, the Americans blandly proclaimed; a welcome one, the Spanish replied with frigid propriety.” [2] The Maine’s appearance in late January 1898 was grudgingly accepted in Cuba; it moored for a few uneventful weeks until the night of February 15, when the ship was rocked by two powerful explosions, setting off the ammunition on board, and quickly sunk at a cost of about 260 sailors and officers dead.

After the explosion, the wreck of the U.S.S. Maine in 1900. Credit: Jackson, William Henry, photographer. "Wreck of the U.S.S. Maine." Detroit Publishing Company ca. 1900. Touring Turn-of-the-Century America: Photographs from the Detroit Publishing Company, 1880-1920, Library of Congress.

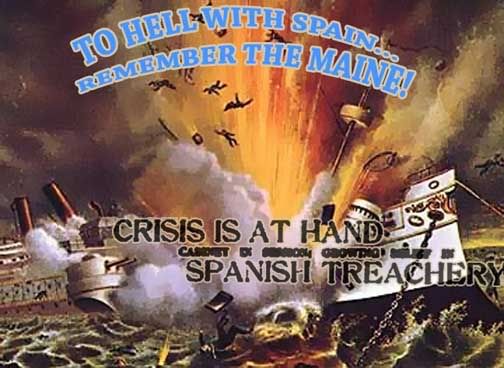

The 2-15 blast was painted at the time as certain Spanish sabotage, ignoring that Spain had no hope of winning a war and no reason for starting one. Yet the “yellow press,” notably the Hearst papers, hyped-up the celebrated battleship’s destruction into a vicious war drive. The famous cry, of course, was “To Hell with Spain! Remember the Maine!” Some, like Samuel Clemens and Andrew Carnegie, were royally pissed at the nascent U.S. imperialism this “splendid little war” evidenced. But despite the protests, “Butcher” Weyler and the bloody sabotaging Spaniards were easily stopped.

The new American possession of the Philippines soon saw its own, larger butchery under the U.S. Army, and Hawaii was annexed as a coaling station to support the war in the Philippines. Puerto Rico has lobbied to become a state of the Union like Hawaii, but with no Pearl Harbor moment of their own, they languish in a semi-colonial status as a military firing range. Cuba’s fate was left complex, with independence so long as the U.S. Navy could maintain a toehold at Guantanamo Bay, which is still in use despite four decades of Castro’s rule, and has of course been back in the news lately as a “legal Black Hole” for the prisoners of WWIV.

As for the Spanish treachery that “started the game” at Havana Harbor and led to all of this, initial inquiries upheld the official story that the Maine was sunk with a submerged mine, presumably Spanish. In 1912 the ship was moved and sunk in the deeper sea, effectively burying the evidence. It wasn’t until the 1970s that the evidence was again dredged up by Admiral Rickover, whose commission decided the blast was probably caused by a coal-room fire, presumably an accident, that set off the ammunition aboard. This is now the generally accepted theory, but I would note that it was a well-timed accident that the Maine should blow up, of all times and places, right after it had docked in soon-to-be-enemy waters for murky reasons, allowing that two-year-old plan to go into effect to the great benefit of U.S. policy.

Theodore Roosevelt, who had sold the President on this plan, resigned his desk job soon after 2-15, going to Cuba and strenuously getting his picture taken on San Juan Hill with his much-publicized “Rough Riders.” As president McKinley rode his swift and profitable victory into a second term in the 1900 election, Teddy joined him as vice president, sworn-in in March 1901. After McKinley was gunned down by a crazed anarchist six months later, Teddy was speaking softly while carrying the big stick of the U.S. presidency with three and a half years ahead of him and no vice president to worry about.

---

Sources:

[1] O’Toole, G.J.A. "The Spanish War: An American Epic 1898." New York. WW Norton. 1989. Pages 100-102.

[2] See [1] O’Toole. Page 21.

No comments:

Post a Comment