THOUGHTS ON WHERE, WHEN, AND WHY

Adam Larson / Caustic Logic

The 12/7-9/11 Treadmill and Beyond

Feb 23 2009

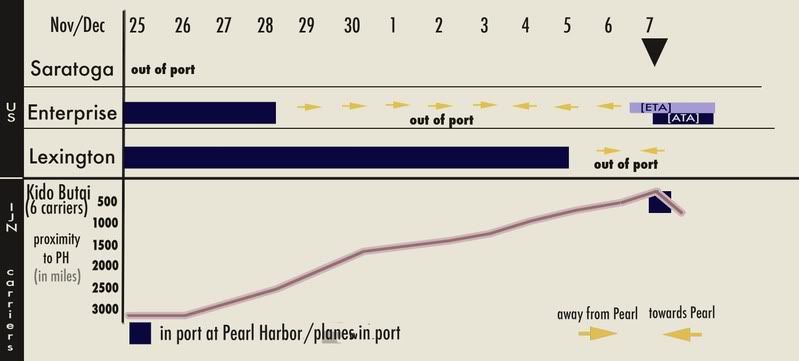

last update 3/29Protection for Projection?As of December 1941, the Pacific Fleet stood depleted, a victim of Atlantic-heavy deployment in solidarity with Great Britain. A scant three aircraft carriers were left between Japan and the west coast: USS Enterprise, USS Lexington, and USS Saratoga. There had been four, until the USS Yorktown was among the quarter of the Pacific fleet transferred to the Atlantic. With the depleted Pacific portion of the Fleet permanently based in Hawaii throughout 1941, these were generally stationed at Pearl Harbor, but when the attack of December 7 came, none of the three was there to be harmed.

As the dawn rose red, USS Enterprise was the closest, just over 200 miles west and on a return journey from Wake Island. The Lexington was much further out, en route to Midway; both were ferrying fighter jets to the islands (see below ). The Saratoga was 2000 miles east and far too busy to help cover their shifts; She had undergone modernization in Bremerton from January to April, "participated in a landing force exercise in May and made two trips to Hawaii between June and October as the diplomatic crisis with Japan came to a head," a Navy history explains. "When the Japanese struck at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, Saratoga was just entering San Diego after an interim drydocking at Bremerton," for unspecified reasons. [1]

While there are apparent reasons for all these movements, the coincidence that Pearl Harbor would be left with absolutely no carriers at just the time of Japan’s sneak attack remains worthy of note and one of the prime areas of controversy in the ongoing debate over what happened and why. While this apparent coincidence cannot provide solid proof of foreknowledge, as a supplement to the already large body of evidence, it's worth an examination.

The much-re-posted

“Pearl Harbor Myths” mini-article sums up this myth “The US carriers were hustled out of port just before the attack, to "save" them for a war that FDR already knew would be dominated by the flattop.” [2] While piece doesn’t do so, many have tackled this myth by arguing that the value of the aircraft carrier for naval warfare was not known at the time. Whatever someone may have claimed to recognize or not at one point or another is immaterial. The carrier in fact became the dominant weapon in the Pacific war, starting with the

six that Japan’s Imperial Navy had sent

towards Hawaii just before the US blithely sent its

remaining two away from there on errands.

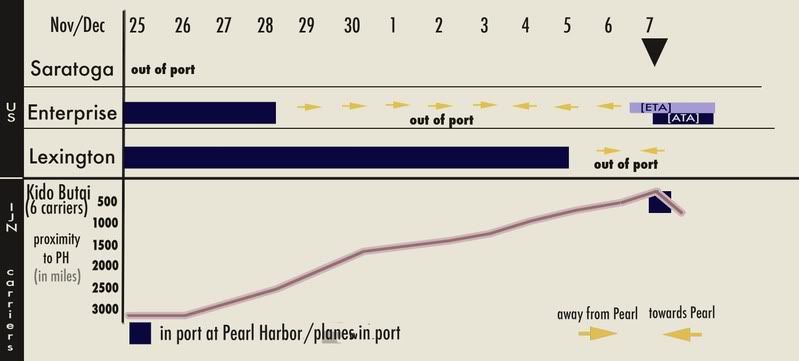

graphic: timeline of carrier activity in and near Pearl Harbor 11/25-12/7 1941. Whichever country supplied them ,there was nearly always at least on carrier nearby. [r-click, new window for larger view

graphic: timeline of carrier activity in and near Pearl Harbor 11/25-12/7 1941. Whichever country supplied them ,there was nearly always at least on carrier nearby. [r-click, new window for larger view Any analyst worth his weight in Styrofoam should have foreseen the craft’s potential value in projecting air power, and any decision-makers involved in any provocation would have access to these views and choose to either ignore to act on them. Whatever was decided and by whatever means, the carriers

were given special consideration and put in a special place, out of the harbor during the attack, and in fact projecting air power – just in the wrong direction.

Becoming a Way StationThere was a method to this madness, if it did ultimately prove a flawed and boneheaded method. The increasing likelihood of war with Japan in the second half of 1941 had caused the US War cabinet to look west and further west, right past Hawaii and the relatively exposed Pacific Fleet, to the distant Philippines, as the most likely flash point. There was a decision to pursue a deterrent bombing capability built up there, to turn the strategic liability into more of an asset, and a serious check on Japan's southward plans. [3] It involved suspending the normal and correct belief that the Philippines were indefensible, and this attitude was circumvented at just the right time to leave Hawaii as a neglected rear area rather than the critical front line.

What was lacking, ultimately, was enough planes to both defend the Philippines and offer a meaningful deterrent to other moves. This paradigm was still being pursued up until December 7, and in the process, Hawaii was neglected and treated, as Kimmel’s intel chief Edwin Layton put it, as ”only a way station to ferry B-17s to build up MacArthur’s forces” on Luzon. [4] When war looked more imminent, the pace of this process only quickened, while the military's joint board “resolved to reject the State Department’s hard-line proposals,” Layton explains, and “opposed “the issuance of an ultimatum to Japan,”” at least until the “imperfect threat" of the buildup was brought up to strength. [5]

Meanwhile, as the US military urged a façade of negotiation to cover their buildup against Japan's ambitions, Washington was shocked to learn of Japanese faux-diplomacy covering for a military build-up against US, UK and Dutch interests. What exactly this information was is a little uncertain, and will get a post of its own. But it became known in DC early on November 26, causing secretary of State Hull to “kick the whole [diplomacy] thing over” with an ultimatum they could not accept, and which he probably knew would spark the war. [6] This was the point when the US effectively decided to switch from talking to military preparations. Immediately after this, during November 26/27, the war council conferred and had warnings sent to all Pacific commanders pointing to possible Japanese attacks almost anywhere but Hawaii. And the two remaining aircraft carriers in Hawaii were requested to boost everything west of there “as soon as possible.” [7]

On November 28, Adm. Kimmel complied and sent the Enterprise, commanded by Admiral Halsey, and its accompanying warships to ferry 12 Grumman F4F-3 Wildcats to Wake Island. The task force began its return journey on December 4, and the following day, Lexington and its retinue set off towards Midway with 18 Vought SB2U-3 Vindicators. [8] These planes were to defend the Islands against Japanese moves and/or provide regional cover for 48 more B-17s to be flown trough there en route to the Philippines on December 7. [9] It's impossible to say if this bombers west strategy was purely a genuine military strategy or, at least in part, a smoke screen to give reason to the neglect of Hawaii - but it served the purposes of the latter, and the former was a miscalculation at best, with that final batch of bombers in fact helping mentally short-circuit radar defense at Pearl Harbor on just the wrong morning!

The Enterprise ETA RebuttalThat attention seems thus drawn away from Pearl Harbor could be seen as supporting the “conspiracy theory” interpretation that Hawaii’s vulnerability was engineered. Further, it only makes sense to suspect the carriers’ locations would be worked into any such plans, and if so, then their absence seems to have been desired during the attack. There are arguments against this, and the best is the Enterprise; as the Pearl Harbor Myths pieces further explains:

“Enterprise was doing her best to get back into Pearl. Her first ETA was Saturday evening, but a storm delayed her. The next time set was 7 AM, 55 minutes before the attack started, but that proved too optimistic as well.”

When you’re dealing with high-stakes illusion, as we may be, a time written on paper does not a real plan make. The science of meterology was nothing then like it is now, but weather prediction was possible. I propose this ETA was fudged with a false presumption of clear sailing but knowing a storm would delay real arrival to (plus six, carry the five…) just

after dawn on “X-day.” But the point gets a little better, that article explains, since the 12/6 arrival was scheduled back in

August, well before anyone could have known about the Japanese plans to barely avoid:

"What really crushes the "carriers hustled out of port" myth is the fact that Enterprise was scheduled to be in port on Dec. 6th and 7th, as shown in the Employment Schedule promulgated in August, '41. No orders were ever recieved to change this. The mission to Wake was planned to coincide with the original schedule so that it would not be known that the island had recieved additional air support. The trip was kept secret, even the loading of the planes had a "cover story".

If it turns out the arrival time was set well in advance, then Dec 6 is a close coincidence that may then have been fudged upward similar to the above but with

shove-off time set hours late, again wrongly presuming clear sailing, to get the carrier arriving back no earlier than the Japanese. Twice the estimates proved “too optimistic” for reality, and these erred guesses, apparently on Halsey's part, are all that gives the sense that one carrier was

supposed to be back in time to join the party. But the reality, of course, is it just missed it, and reality is what matters to me.

Thrift or Thrown Game?While I admit this fudged ETA business is quite speculative, it would serve to make the carrier absence look less suspicious, and give a hand to those who'd like to explain away these clues. That it does look dubious is testified by conspiracy theorists latching onto the “myth,” a natural impression which may have been predicted as a down-side to mitigate. If they knew it would look off, this raises the fair question of

why the planners would risk such a move in the first place - carriers were valuable and scarce at the time, but ultimately expendable and easily replaceable in the post-attack climate. Given their utility alone it hardly seems worth the risk to have

all of them out when at least one lost would look more natural. Thus “saving’” all three could hardly have been simple thrift, and this is likely only a secondary explanation. *

An obvious

primary reason to consider, in keeping with the general thrust of this investigation, is to deplete Pearl Harbor's defenses. Minus the carriers and their decks full of fighting planes, the Japanese raiders quickly decimated almost all the remaining ground-based aircraft, which had been bunched to avoid against dread sabotage. The Enterprise returned 12 planes lighter but still holding most of its own fighters and bombers, which were close enough as the attack unfolded that they actually took part in the latter half of the defense. What kind of role they’d have played if fully in port is unsure; as it was, it seems Enterprise planes only took down one Japanese bird of the 29 lost in the attack, while losing several to enemy and understandably jumpy friendly fire. [10]

The people in the know seem to feel this carrier movement impeded the defense. Fleet intel chief Layton later summed up the effect of the carriers’ departure in that accidentally ironic way that could, with the slightest shift of view, mean exactly its opposite :

“That Stark, as well as Marshall, agreed to reduce the fighter strength at Pearl Harboor by half, and to run the risk that “there will be nothing left at Hawaii until replacements arrive,” was in itself evidence that whatever warning of Japan’s war moves had been received in Washington, it contained no hint of an attack on Pearl Harbor.” [11]

Prophecy Fulfilled So with the defense aspect of carrier placements duly rendered ambiguous, let's return to the earlier point about the understood role of the carrier; if it was not seen prior to 12/7, it surely was after, and early probing into its potential can be seen in the curious “Doolittle Raid” of April ’42. It was just two weeks after December 7 that the President first told his war cabinet he wanted Japan proper bombed as soon as possible - partly to boost US morale but more so to shake Japan’s, and specifically as an answer to Pearl Harbor. ‘Sure, you can hit us in Hawaii,’ the message seemed to be, ‘but we can hit you at home.’ Lacking land bases close enough this early in the war, the raid was to be launched from a carrier, itself a move widely thought impossible for the larger bombers that would be needed. But after months of practice with B-25s and simulated carrier decks, they made it work, launched and rained some token destruction on Tokyo, and gave Japan its first hint of their grim future before crash-landing in or near free China. The just-completed carrier USS Hornet provided the deck for the raid, and the USS Enterprise showed up on time for its assigned escort duty on this symbolic revenge mission. [12]

By the time the raid was being planned, the ‘derelict’ Adm. Kimmel had been sacked and replaced with new Pacific Fleet commander Adm Chester Nimitz, the prophet and eventual hero of Pacific carrier warfare. Nimitz was destined for the spot, and seems to have foreseen more about the Pacific War than flat-top dominance. Earlier in 1941, he was tapped for command of Pacific Fleet, but perhaps on good advice from, say, Adm. Richardson (the outgoing CinCPAC to be replaced), turned it down, leaving the spot open for Kimmel. According to Nimitz’ son, in a 1996 History Channel documentary, the admiral said at the time:

"It is my guess that the Japanese are going to attack us in a surprise attack. There will be a revulsion in the country against all those in command at sea, and they will be replaced by people in positions of prominence ashore, and I want to be ashore, and not at sea, when that happens.” [13]

---

* To add to the thrift reason, we must consider not only the carriers but their escorts. I did a little research looking at this site on what was present on 12/7:

http://www.history.navy.mil/faqs/faq66-2.htm

and this one on what was away with the carriers:

http://www.history.navy.mil/faqs/faq66-9.htm

In Port:

Battleships – 8

Heavy Cruisers – 2

Light Crusiers – 6

Destroyers –30

Total = 46 war ships

Additional auxiliary ships, minesweepers, submarines, tenders, etc… 55

With the carrier task forces:

Two carriers, obviously

6 Heavy Cruisers

14 destroyers (split 9/5)

total = 22 war ships

So 3/4 of the heavy cruisers were absent, and about 1/3 of the destroyers. A 22 ship-reduction leaving 46 behind is about 1/3 detachment in sheer numbers, which is itself significant. About the quality and value of the classes of ships relative to each other I don't know - would this be the most valuable third? Layton's assessment [And I was There, p 263] is a little exaggerated, but informative:

"At this point [Dec 5-7], the disposition of of Kimmel's forces was as follows: All the carriers were at sea with specific missions. All the heavy cruisers and more than half of the fleet's destroyers were at sea protecting the carriers. Only the battle force - the old, slow battleships with their escorts of light cruisers and destroyers - was still at Pearl Harbor."

---

sources[1] USS Saratoga CV 3. From: Dictionary of American Fighting Ships, published by the Naval Historical Center.

[2] “Pearl Harbor Myths”

[3] Layton, Edwin T. with Roger Pineau and John Costello "And I Was There": Pearl Harbor And Midway -- Breaking the Secrets."New York. Quill. 1985. P 171.

[4] Layton et al. P 170.

[5] Layton et al. P 177.

[6] Layton et al. PP 198-206

[7] Layton et al. 210

[8] See [1]

[9] Layton et al. 209

[10] Wikipedia. USS Enterprise (CVN-65)

[11] Layton et al. P 210.

[12] Wikipedia. Doolittle Raid.

[13] Conservapedia. McCollum Memo.