WHERE MOïSE AND I DISAGREE

Adam Larson / Caustic Logic

June 10 2009

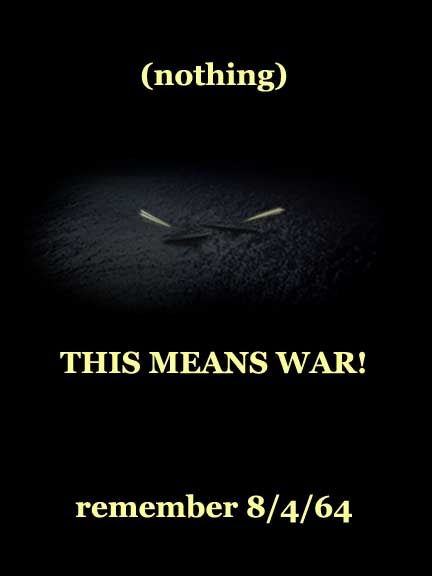

Since it’s all I have to offer anyway, I will momentarily skip out on further analysis and state my opinions on the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, Okay, I’ll cite a few supports, but the point is this might suffice as my final post on the subject, which is quick, since I’ve only put up three previously. I'm not even tempted to make any cool graphics for this one, after looking at the endless nonsensical scribbles Edwin E. Moïse had to wade through to re-construct the reality behind the two-hour circus of blunders.

From a cursory skim of some of the evidence, I find the faint possibility that some real vessels firing real torpedoes were involved, at least in the first part of the reported two-hour attack. This is the only aspect that might mean anything new; it would to me strongly imply a false flag operation involving RVN torpedo boats on a heavily-modified OPLAN 34-A raid. However, such a possibility raises many questions, and my guess is that it would not hold enough water to bother looking into it.

Aside from this intriguing distant possibility, I see little need to examine the actual non-events of August 4, 1964. All reputable and most non-reputable sources by now agree, from the overwhelming body of evidence, that no attack took place where one was claimed and aggressively pushed as the pretext for an endlessly escalating yet endlessly losing war of choice. Among all the surviving then-experts at NSA, CIA, Pentagon, various fleet commands, etc., one can find no surviving belief in the reality of this history-making engagement. Moïse’s Tonkin Gulf and the Escalation of the Vietnam War cites “profoundly disturbing” attempts by the U.S. Navy, as late as 1986, to pass the alleged attack off as real with an impressive-looking official history. [p xii] By now however even the Navy has given up the cause; as researcher John Prados explained in 2004, “the history of U.S. destroyers carried on the Navy's official website no longer contains any reference to a naval engagement having occurred on August 4.” [Prados]

Remaining questions encompass the area of unprovables – what did the active parties think and believe as they set this faux pas into motion? Opinions will differ, as mine and Moïse’s do; he feels the second attack reports were “not a deliberate fabrication” by the United States, as the North Vietnamese charged at the time. “I was quite sure that President Johnson had been making an honest mistake when he bombed the DRV in “retaliation” for an action the DRV had not committed.” [p xv] That author admits being embarrassed explaining this view to his Vietnamese hosts, who surely rolled their eyes, mentally at least. I’m not convinced he really believes that interpretation, what with former White House advisors and top generals and the like to interview, it might serve one well to avoid making such bold accusations – even if they seem warranted.

Of course he was also speaking with much of the epically befuddled destroyer crews who honestly believed the string of BS they reported that night. He doesn’t seem to feel anyone consciously made up anything, and proceeds examining how such massively erred reports originated absent any dishonesty. I’ve already expressed the possibility that the destroyer crews consciously made up the attack, and this would explain the consistency of error that reigned during the two hours an impossible attack was being reported. This is not a case I’ve seen anyone else make, and of course it’s entirely possible that an amazing string of errors in the tense climate triggered the hysteria after all. As the Pentagon set about constructing the story they’d stick with, the pressure from Washington to deliver an attack may have effected the crew only subconsciously, making their continued misinformation just more honest mistakes. Human memory can be, or can be presumed to be, infinitely strange.

Whatever the mindset behind the reports, it’s the pressure from above that matters - the suction of retaliation already in progress, that pulled out a bit more evidence, to the extent it even mattered once the wind was blowing that way. The force of that shift is clearly illustrated by President Johnson’s haste to hit back before figuring out whether there was really an engagement or not on August 4. The first draft of the Tonkin Gulf Resolution was done up and discussed with some in Congress within nine hours of the first reports, and retaliatory air strikes underway five hours after that. And those were considered far behind schedule.

The military moved along the path blazed by the President’s decisive headlong rush to war. From what I’ve read, they did this with private reservations about the pretext, but otherwise with gusto and enthusiasm and no outward doubt. The first order of business was too get hostilities opened, the second to establish their collective cover story for the pretext, which wound up being a half-ass amalgamation of carefully screened evidence. This is the essence of fabrication, in its original sense. Separate threads were somehow brought together and were consciously woven by a pre-designated pattern; a “fabric” was undeniably formed, and a major and brutal war was then sewn from that fabric.

But was it deliberate? Moïse found “no evidence,” nor any “reason to suppose” anyone in the Washington leadership had any doubts about the incident during the crucial three days between its occurrence and the passage of the Tonkin Gulf Resolution. He did find evidence that President Johnson had passed from doubts about the attack’s veracity to little doubt it was all bogus within “a few days” of the incident, with his famous “flying fish” comment. [p. 210-211] Defense Secretary Robert MacNamara was initially and for a long time publicly certain their pretext was sound, privately expressing some doubts years later, and only deciding out loud that it was probably not real in 1995. He was clearly aware from at least mid-September 1964 that the President didn’t believe his own case, according to recorded conversations between the two declassified in 2001.

My opinion is if these people were inclined to any caution, they must have at least suspected the attack was unreal, grossly exaggerated, unverified, or something other than what they presented it as. Downplaying genuine doubts and presenting something other than what happened is, in a sense anyway, “deliberate fabrication.” Again, there is no way to prove whether LBJ, MacNamara, any of their subordinates or advisers or the generals and planners and escalators or the destroyer crews themselves knew they were selling bullshit. They might have honestly thought it was something wholesome and real, not realizing the stink. In my opinion, it all comes down to how fucking stupid you believe these guys were.

Sources:

Moïse, Edwin E. “Tonkin Gulf and the Escalation of the Vietnam War.” Chapel Hill (University of North Carolina Press). 1997. 255 pages

Prados, John. Essay: 40th Anniversary of the Gulf of Tonkin Incident. National Security Archive, George Washington University. Posted August 4 2004. http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB132/essay.htm

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment