[Pan Am 103 Series]

Adam Larson / Caustic Logic

September 30 2009

last update 10/3

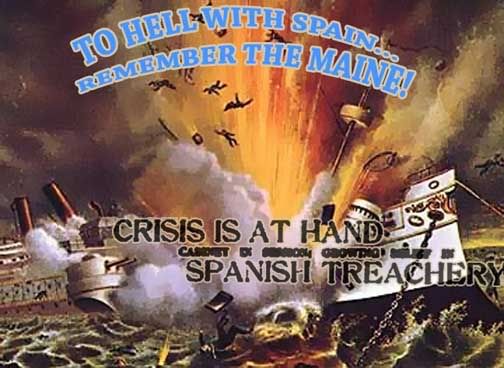

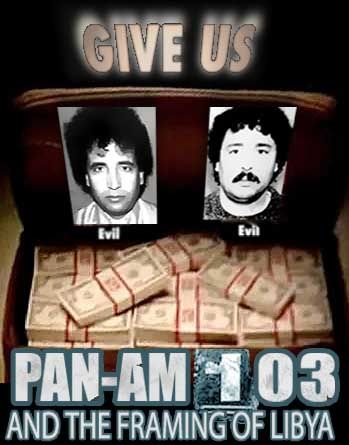

Following the December 1988 Pan Am 103 bombing, the congruence of original clues that the investigation were following pointed quite clearly in one direction: to the Syria-based PFLPGC group, apparently commissioned by Iran as in-kind retaliation for the USS Vincenes incident. By late 1991 the focus had long-since shifted and had come to the indictment of two Libyans, sparking a long-simmering political dispute capped with a guilty verdict and life sentence for one of them (al Megrahi) handed down nine years later.

The timeline in between is a little murky, but the investigative shift appears to coincide, roughly, with the 1990-91 Gulf War. In this context, Iran was a force one wouldn’t want too much quarrel with while focusing on their more built-up neighbor. Syria, on Iraq’s other flank, had agreed to assist the U.S effort in line with the general mindset of the Arab League. Pursuing a terror group sponsored by Damascus over the bombing would be politically inconvenient. Coincidentally of course,as case expert Paul Foot noted, after the invasion of Kuwait in August 1990, “the official view of the disaster was that Syria had, in Bush's typically elegant phrase, 'taken a bum rap on this'; and that the people responsible for Lockerbie came from the one Arab state which had denounced the US role in the Gulf War: Libya.”

Col. Gadaffi's regime was already a convenient enemy known for supporting anti-American terrorism, and had their own poignant reasons for revenge – the death of scores of Libyans, including an adopted daughter of Gadaffi’s own, by U.S. bombing in 1986. And most of the clues pointing to a shift in blame started emerging, all on their own it might seem, well before the open saber rattling in the Gulf. Foot noted one of the earliest harbingers of a course change “in mid-March 1989, three months after Lockerbie,” when “George Bush rang Margaret Thatcher to warn her to 'cool it' on the subject.” Could this have been triggered by the Gulf War’s alliance system?

A 2008 BBC documentary agreed that as of mid-1989, “Britain’s biggest mass murder investigation looked like it was stalling,” unable to find the hard links to the PFLP necessary to continue. Countering the cynical conspiracy theorists that blame Gulf War politics, they report that clues pointing to Libya started coming in “from August 1989, twelve months before the invasion of Kuwait.” This, it went on, was an anomalous report from Frankfurt Airport suggesting an unaccompanied bag from Malta had gotten onto PA103 there; Malta points straight to Libya, Tripoli’s “backdoor to the West,” as the video puts it.

The most important clue would be the MST-13 timer fragment, identified in mid-1990, linked via its maker Mebo to Libyan intelligence. If the Libyans were not guilty, as seems the case, it’s almost necessary the fragment was planted. According to official paperwork (which is actually pretty dubious), this was no later than mid-May 1989, when it was first catalogued. Barring altered records, a plan to implicate Gadaffi’s team had to be in execution this early. Again, could this first huge step towards the Libyan guilt myth have been triggered by the coming showdown with the Butcher of Baghdad? Surely a rational thinker is looking here for less obvious outside reasons to look elsewhere, or simply... the evidence emerging?

Any explanation that relies solely on the coalition-building running up to Operation Desert Storm is bound to miss valuable leads; there had to be more at work with how the onetime PLFPGC suspects were handled; at least one of them was reportedly a CIA asset, and he and others had been released from prison with suspicious ease just after getting caught with bombs similar to what brought down 103, but shortly before it was brought down. Something looks embarrassing there no matter who you want to look at instead. And for what it’s worth, the pros of leaning against Libya in particular would be known and considered independently. But finally, I contend Gulf War-type thinking could also be a strong or central factor, even for the earliest of alleged shenanigans, and helps flesh out the "motive" category for any speculation.

This can be seen at the level where things seem almost "scripted" in grand strategic sweeps, a changing geopolitical zeitgeist some are privy to well before others. This timeline of the Iran-Iraq War shows the zeitgeist of mid-1988 was of the United States and its armed proxy Iraq working in tandem, partly intentional, partly accidental (or rather, the USS Vincennes incident) against a common foe. Like a tsunami the hits came down on Iran and its people, subduing Tehran into a weaker hand at the ceasefire finally agreed in late July. Almost exactly two years later the US was fighting against Iraq.

What happened in between? Most run-of-the-mill Gulf War timelines start with late May 1990 and Iraq's charges of economic warfare against Kuwait. One might guess some foreshadowing being picked up by American minds prior to this, but it's more than just shadows. The background I needed I already learned reading Ramsey Clark's The Fire This Time (1992). It’s a slanted work to be sure, but quite informative in its way. His intro timeline [p xxiv-xxv] goes into some relevant details missed by the ones I was seeing on the internet. Let's follow it backwards from May 1990 to see how far back the mindshift towards Iraq as the enemy goes:

February 1990 – General Schwwarzkopf testifies before the Senate of the need for the United States to increase its military presence in the Gulf region. He warns that “Iraq has the capability to militarily coerce its neighbors.”On the evidence and time of the "dramatic" attitude shift, Clark started with the Iraqi chemical weapons attack on Halabja, March 1988. The horrifically illegal toxic slaughter of thousands of Kurds, many adults of whom had collaborated with the iranians, was largely ignored by western media and governments at the time, even after large Kurdish protests at the UN. [p 19-20] The zeitgeist of mid 1988, or simple ignorance, could explain these oversights.

January 1990 CENTCOM headqyuarters stages a game entitled Look, which tests War Plan 1002-90.

1989 War Plan 1002, originally conceived in 1981 to counter a supposed Soviet threat to the Persian Gulf, is adjusted to designate Iraq as the threat to the region. The plan is renamed War Plan 1002-90.

1988 [...] A ceaefire agreement is signed between Iran and Iraq in August. U.S. policy towards Iraq shifts dramatically. The Center for Strategic and International Studies begins a two-year study predicting the outcome of a war between the United States and Iraq.

Clark then noted it was on September 8, just three weeks after the Iran-Iraq cease fire, that the U.S. finally decided to announce that their erstwhile proxy had gassed a group of people that happened to be tied by ethnicity. A State Department spokesperson referred to the attack(s) (vaguely related) as “abhorrent and unjustifiable.” The same day, Iraq’s Foreign Minister was in town to meet Secretary of State Schultz, and had the chance to be barraged with unexpected questions and to respond weakly. Within a day of this well-placed slap. “the Senate unanimously voted to impose sanctions” on Iraq. Somehow this “never became law” but was seen as “a threat and a humiliation” by Iraq, and ultimately a harbinger of things to come.

So was the necessary mindset there and strong to make nice with Iraq's enemies even four months before the Lockerbie bombing? It was there, if requiring serious foresight to pick out early on. But the new zeitgeist had surely grown some in currency by, say, March '89. This does not mean it's the reason the blame shifted, but shouldn't be scratched as one of the birds to be killed with this stone.

No comments:

Post a Comment